I started canning tomatoes from my garden at least 10 years ago. Perhaps 11 or 12 years ago.

At the time I started, I did some research on the Internet and got comfortable with a method of canning that essentially requires the tomatoes to be boiled down and blended into a coulis or semi-sauce consistency (for at least 45 minutes, usually much more – for example, today, I simmered the tomatoes for 3 hours) and then pouring the cooked/blended liquid into sterilized jars with salt and a little bottled lemon juice. This approach puts boiling liquid into hot jars with boiled lids, but does not require boiling the jars once they’ve been filled.

Sometime in the interim, the English Internet got much more concerned about food safety with canning. For example, the USDA Guidelines on Tomato Canning state that all canned tomato preparations need to be processed in a water bath or pressure cooker (even if you’re dealing with a boiled preparation).

But, there are plenty of Internet resources in French and Italian (as well as a few in English) that still swear by this style of canning as what multiple generations of families have historically done with no problems.

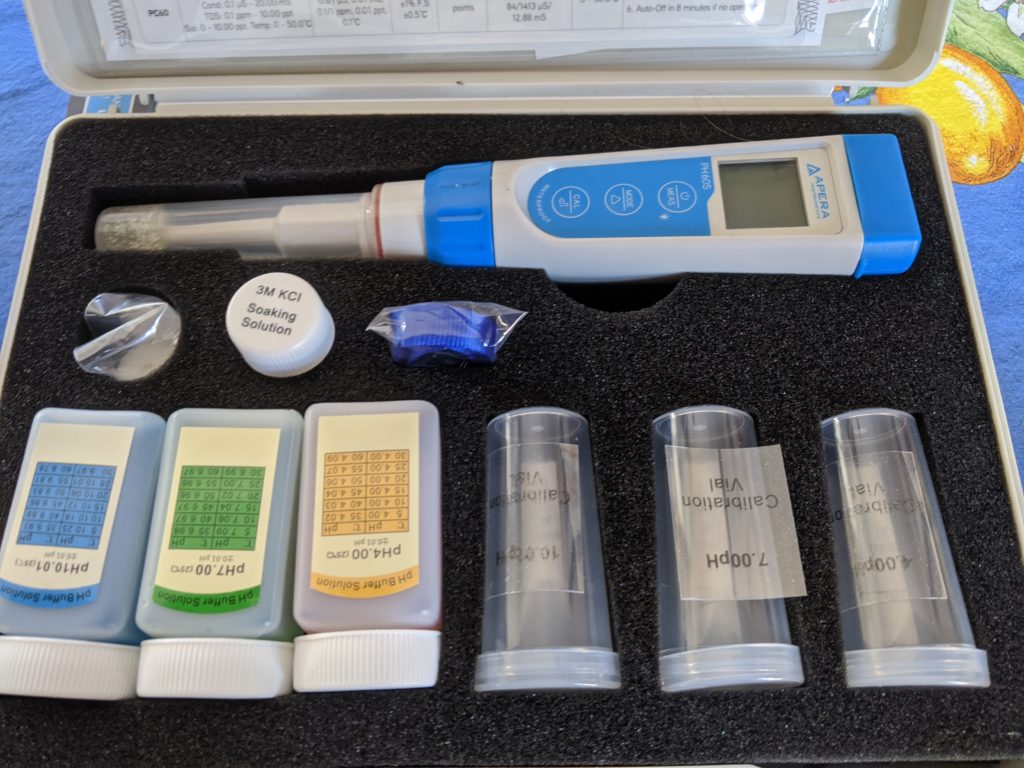

After a few years of the annual debate about whether I needed to change my approach because the Internet says so, in this time of COVID-19 stay-at-home, I decided to buy a proper pH meter to figure out if my canned preparations were below the 4.6 pH cutoff of acidity, below which, C. botulinum bacteria cannot grow.

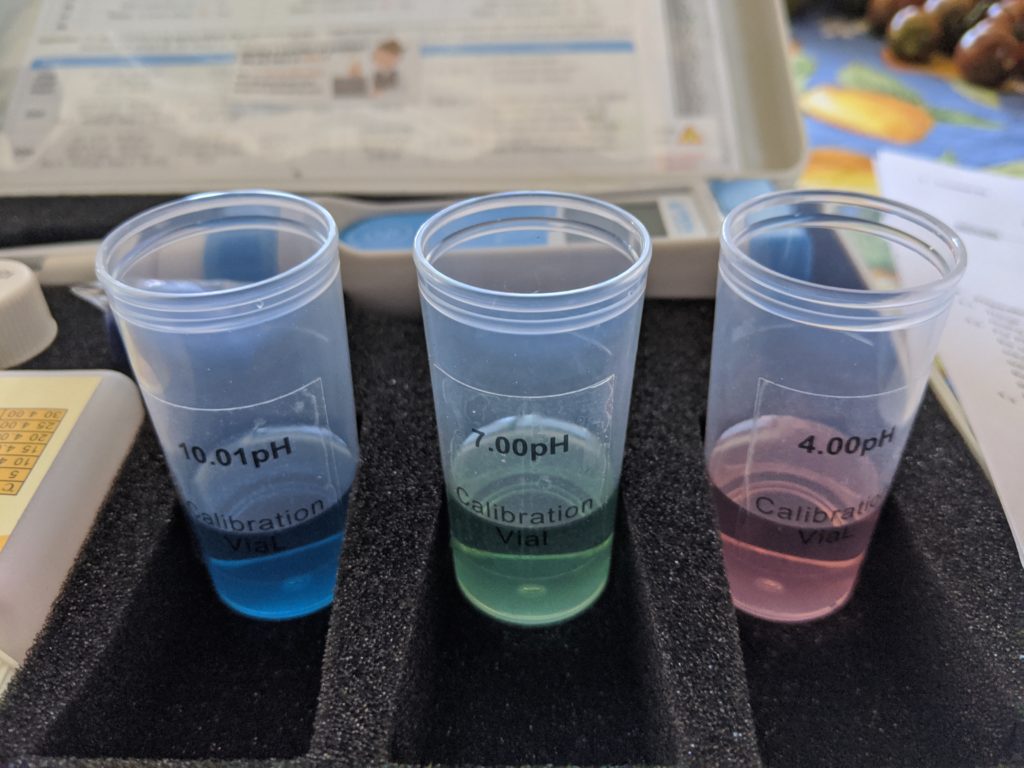

First, I ordered my new science toy. Then, I calibrated the pH meter according to the instructions. At first I thought it may be broken because the distilled water kept testing at a pH below 6 and I thought we all knew that water was supposed to be a pH of 7. Welp, turns out that’s true immediately after distillation, but when it sits around exposed to the atmosphere, distilled water absorbs carbon dioxide and becomes slightly acidic with a pH of around 5.8.

Relieved that my new toy wasn’t broken, I proceeded to test the pH of the raw tomatoes I was going to use to make the sauce — I took 3 samples for most of the tomatoes and there was some variance, even within the same piece of fruit. My pH meter is rated to be correct to within 0.01 pH. Here are the readings:

- White Oxheart: 3.90, 3.83, 3.97

- Snowberry: 3.90, 4.37, 3.96

- Amish Salad: 4.39

- Kentucky Beefsteak: 4.01, 4.15, 4.17

- Golden Globe: 4.61, 4.86, 4.41

- Isis Candy Cherry: 4.51, 4.37, 4.83

After 1 hour of boiling, the sauce tested at 3.96 & 3.99. After 2 hours of boiling, I used the stick blender to break up the remaining chunks of flesh and skins and tested the pH immediately after blending, where it measured 4.09 & 4.08.

After 3 hours of boiling, I tested the sauce and it measured 3.98 & 4.01. At this point, I was feeling pretty good. Since pH is a logarithmic scale. A pH of 4 is significantly more acidic than 4.6.

For fun, I tested the lemon juice and it measured at a pH of 2.54 and 2.53. I put some lemon juice in each of the quart jars as well as some salt, filled the jars, and then stirred the mixture in each jar with a chopstick before my final pH measurement.

The five quart jars measured 3.95, 3.69, 3.88, 3.85, and 3.78. All well under the 4.6 danger point. So, I cleaned the rims, put the boiled lids on top, tightened the bands, and turned the jars upside down to cool. I am now very comfortable that the science supports my traditional no-water-bath approach to canning tomato coulis from my garden.