People are often surprised to learn that employers sometimes try to claim ownership in an employee’s intellectual property for inventions that are not related to their job.

Like many attorneys who work with startup companies, I am a huge fan of California Labor Code 2870. This law says that an employer in California may not require an employee to assign IP created by the employee during the time of that employee’s tenure if it’s created on the employee’s own time, without using the employer’s resources (use your own non-company owned computers and network connectivity, people!), and so long as it is not related the company’s research and development.

An untold number of start-up companies have been created by founders in California who did the initial IP development on the side while holding down a salaried job with an employer. Statutory protection of inventor rights in independent inventions (alongside a prohibition against most post-termination non-competes) is often cited as one of the reasons the vibrant startup ecosystem in Silicon Valley and throughout California exists.

Unfortunately, I’ve seen many contracts where employers purported to own all (or much more than California allows) of the intellectual property created by the employee during their employment. Thanks to California Labor Code 2870, the overreaching portions of those contracts are unenforceable in California. In California, founders who create IP for their next startup (or FOSS developers who work on unrelated FOSS projects) can feel comfortable that the IP created in their moonlighting, hobbies, side hustles, etc. are their own property if they follow the rules.

I knew that a few other states had similar inventor rights statutes on the books, but it had been a while (let’s be honest, probably a decade) since I’d looked into it generally. So, in preparation for a lecture I was giving to new engineering graduates (with job opportunities all over the United States), I did some Internet searching.

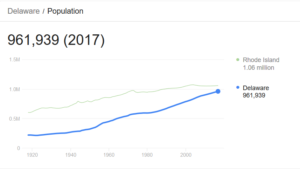

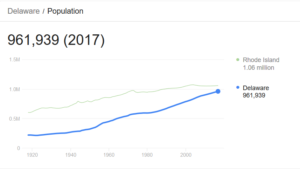

I was very surprised to learn that Delaware has an inventor rights statute. How had I not heard about/internalized this before?

As you may know, Delaware has more corporate entities than people.

According to the Secretary of State’s 2016 Annual Report, there were more than 1.2 million corporate entities registered in Delaware, and at that time, more than 2/3 of the Fortune 500 were Delaware corporations.

In other words, Delaware is the most popular US state for corporate formations and many, many companies (especially big public companies) that employ lots of people are Delaware corporations.

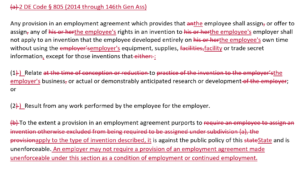

Because of this, many of the contracts with overreaching IP terms I’ve reviewed in the past were with Delaware corporations. Most of those employees were not working *in* Delaware, and I’ve always looked to the labor code of the state in which the employees were employed. However, if a company chooses to avail itself of Delaware law by incorporating there, it is subject to Delaware law, public policy, and jurisdiction. I don’t know why it hadn’t occurred to me that all employees who work for a Delaware corporation can point to 19 DE Code § 805 (2017) :

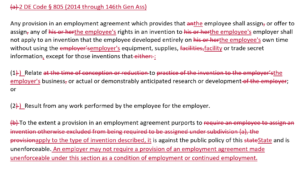

Any provision in an employment agreement which provides that the employee shall assign or offer to assign any of the employee’s rights in an invention to the employee’s employer shall not apply to an invention that the employee developed entirely on the employee’s own time without using the employer’s equipment, supplies, facility or trade secret information, except for those inventions that:

(1) Relate to the employer’s business or actual or demonstrably anticipated research or development; or

(2) Result from any work performed by the employee for the employer.

To the extent a provision in an employment agreement purports to apply to the type of invention described, it is against the public policy of this State and is unenforceable. An employer may not require a provision of an employment agreement made unenforceable under this section as a condition of employment or continued employment.

Those of you who know California Labor Code 2870 will find this language very familiar. The Delaware version is just a slightly different version of the same law. In general, I think the Delaware drafting is slightly tighter, although I don’t like the lack of the “at the time of conception or reduction to practice” limitation. I do, however, love the clear final sentence, which I will be using to argue against over-reaching IP provisions in Delaware corporation employment agreements.

Sure, a greedy corporation could claim that even though Delaware won’t enforce an egregious IP assignment, perhaps another state where the employee is working will. But it’s not a good look for the employer to intentionally go against the public policy of the state where they are availing themselves of corporate protection. Most employers don’t sue to acquire employee IP, but rather point to contracts and demand assignment from employees who are scared to incur legal fees. I suspect they’ll be even less likely to sue if they realize their employee is aware of a public policy of Delaware that specifically prohibits the contractual term they are trying to enforce.

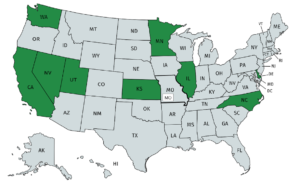

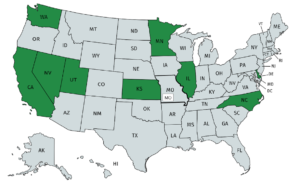

California adopted Labor Code Section 2870 in 1979. Delaware adopted Labor Code Section 805 in 1984. I’ve confirmed that as of today, at least the following states (I need to do a 50 state survey) have an inventor rights statute:

Including the weight of all of the Delaware corporations plus employees working in and corporations incorporated in all of the other green states above means that inventor rights statutes are not a leading-edge policy that only applies to a few select states and companies. Inventor rights is actually a legal norm that applies across the majority of large technology employers in the United States, and even employers who are not expressly required to respect them should consider that failing to do so is likely to cause them to lose out on top talent in their employment pool.

For more information, see the redline below for a detailed display of the differences between California’s and Delaware’s statutes, or click on the links to see the specific statutes for each state.

California https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=LAB§ionNum=2870

Washington http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=49.44.140

Nevada https://law.justia.com/codes/nevada/2010/title52/chapter600/nrs600-500.html

Utah https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title34/Chapter39/C34-39_1800010118000101.pdf

Kansas https://law.justia.com/codes/kansas/2006/chapter44/statute_18289.html

Minnesota https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=181.78

Illinois http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs3.asp?ActID=2238&ChapterID=62

North Carolina https://www.ncga.state.nc.us/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/PDF/ByArticle/Chapter_66/Article_10A.pdf

Delaware http://delcode.delaware.gov/title19/c008/index.shtml